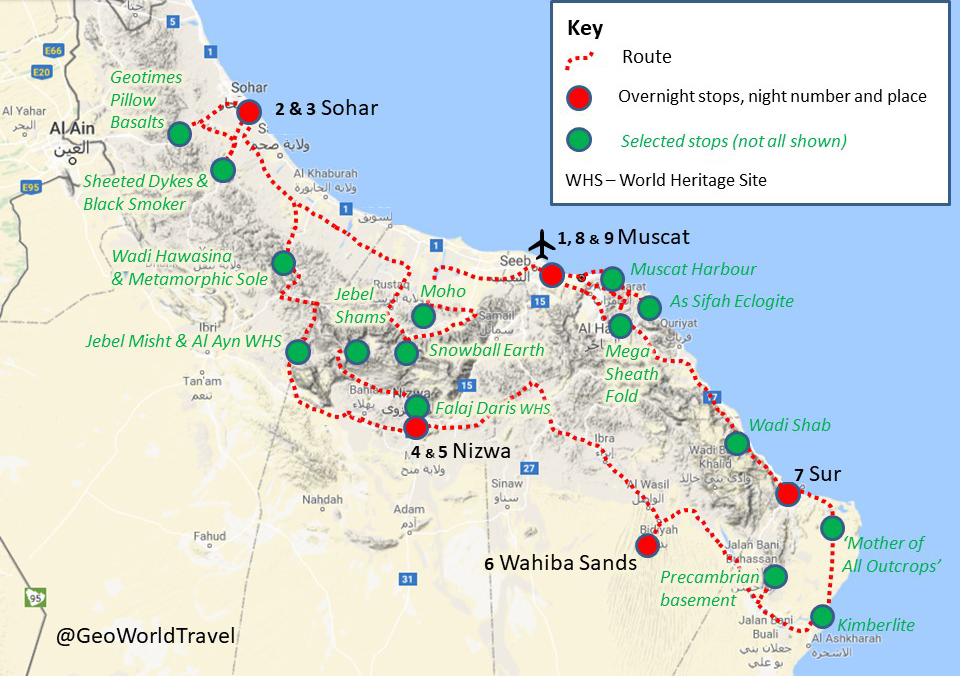

We’ve been lucky to explore some incredible geological landscapes over the years, and our 2026 trip to Oman was one of the most remarkable yet. From walking ancient sections of ocean crust and mantle to standing on Snowball Earth deposits and tracing the world’s largest ophiolite, this adventure took us deep into the Earth’s history and across some of the country’s most stunning scenery. Our photo diary shares some of our favourite moments from this unforgettable voyage through one of the planet’s greatest geological playgrounds.

Day One: Arrival in Muscat

Touchdown in Oman’s vibrant capital, settling in and meeting the group ahead of the geological journey to come.

Day Two: Moho, Snowball Earth & Ancient Stromatolites

Exploring Wadi al Abyad’s incredible crust-mantle boundary, Snowball Earth cap carbonates and ancient stromatolites.

Left: Clark and Marty touch the Moho (Mohorovičić discontinuity) – the boundary between the Earth’s crust and mantle – at Wadi al Abyad.

Top right: Charles points to the contact of the cap carbonates and the Snowball Earth diamictites). This boundary represents a time when the earth changed from a global glaciation to a super-greenhouse effect in a geological instant. It is also the boundary between the Cryogenian and Ediacaran periods.

Bottom right: Marty stands on the unconformity contact between Permian-aged beach deposits and Ediacaran-aged limestones. Directly below her, the fossils of stromatolites can be seen in the Ediacaran-aged rock.

Left: An angular unconformity with Permian rocks overlying Ediacaran rocks in Wadi Bani Kharus.

Right: Zuha Gossan, a fossilised black smoker which is part of the Semail Ophiolite.

Left: The group examines metalliferous sediments (umber sediments). These are iron- and manganese-rich deposits formed in association with black smoker hydrothermal vents. The metal enrichment occurs when hydrothermal fluids mix with cold seawater, causing dissolved metals to oxidise and precipitate out of solution.

Right: Boninite pillow lavas with a globular/spherulitic texture. Boninites are chemically unstable, water-rich magmas. When they erupt underwater as pillow lavas, they cool so fast that they form glass which then crystallises explosively into radiating spherulites and globular textures. Boninites are a rare high Si, high Mg, but low Ti type of lava. They are nearly always found above subduction zones like the Izu-Bonin arc south of Japan, are a key piece of evidence that the Semail Ophiolite of Oman formed above a subduction zone.

Left: The pillow basalts at Wadi al Jizzi are widely regarded as one of the best pillow basalt outcrops in the world. The basalts were erupted directly onto the seabed, where rapid cooling by seawater produced characteristic pillow lava structures.

Right: The remains of a white smoker that originally formed on the ocean floor. This hydrothermal system differs from a black smoker because it formed from cooler fluids (150°C rather than 300°C). As a result, it contains much less metal mineralisation but is rich in opaline silica.

Day Three: Mid-Ocean Ridge Rocks & Pillow Basalts

Seeing fossilised black smokers, sheeted dykes and arguably the world’s best pillow basalt outcrops.

Left: The GeoWorld Travel group in Wadi Murri observing the contact between the Semail Ophiolite nappe and the Hawasina nappe

Top right: A view at Wadi Murri where multiple geological units can be seen plunging beneath one another. To the left, are the Cretaceous autochthonous limestones of the Arabian continental margin. These rocks were deposited on the stable Arabian shelf and represent the continent itself. In the centre of the view, these Arabian margin sedimentary rocks are seen plunging beneath the Hawasina Nappe, which is composed largely of deep-marine slope and basin sediments that were scraped off and transported during convergence. And to the right, the Hawasina Nappe itself disappears beneath the Semail Ophiolite nappe, representing oceanic crust and upper mantle that were emplaced onto the continental margin during Late Cretaceous obduction.

Bottom right: A view of Jebel Misht, in the background, with Al Ayn Beehive tombs in the foreground. Jebel Misht is a striking and distinctive peak in the Hajar Mountains and is interpreted as part of the Haybi Nappe. Its extraordinary appearance is defined by its near-vertical north face, rising roughly 1,000m.

Left: Inside the Al Hoota Cave, which is the largest show cave in Arabia and one of Oman’s most important karst features. It is developed within mid-Cretaceous limestones and dolomites of the Wasia Group (Albian–Cenomanian age), which were deposited on the shallow-marine carbonate platform of the Arabian continental margin. The cave formed as slightly acidic groundwater flowed through the rock along tectonic fractures and bedding planes, gradually dissolving the limestone and enlarging fractures into chambers and passages. This process took place over hundreds of thousands to millions of years, driven by regional uplift, fracturing, and changes in groundwater level.

Right: The GeoWorld Travel group enjoying the geology museum at Al Hoota Cave.

Left: Wadi al-Nakhr is one of the most dramatic landscapes in Oman and is widely known as the Grand Canyon of Arabia. The canyon cuts up to 1,500 m into the Arabian continental margin, exposing an exceptional autochthonous Jurassic–Cretaceous limestone and dolomite sequence deposited in warm, shallow tropical seas. These massive carbonate units form near-vertical cliffs that clearly record the geological history of the Arabian platform. The canyon was carved by long-term river erosion and karst processes, driven by uplift of the Hajar Mountains and guided by fractures and bedding planes in the limestone.

Right: A figure carved on Hasat Bin Salt, also known as Coleman’s Rock after geologist Robert Coleman highlighted it in the 1970s. It is a 6m high rock located on the wadi bed beneath the impressive landmark Jebel al Qal’ah and is regarded as one of the most important rock art monuments in south-east Arabia.

Left: The GeoWorld Travel group at Falaj Daris. This is part of the Aflaj Irrigation System of Oman UNESCO World Heritage Site, one of the world’s most important traditional water-management systems. Some aflaj in Oman are up to 4,500 years old, and they are widely regarded as a key factor in the development of settled society in the region, allowing nomadic communities to establish permanent agriculture and towns.

Right: Plagiogranite (trondhjemite) can form due to extreme fractional crystallisation of mantle melt at the boundary of the gabbro magma chamber and sheeted dyke complex. Here, Hilary points to a basaltic xenolith within the plagiogranite.

Day Four: Al Hajar Traverse & Ancient World Heritage

Crossing the dramatic Al Hajar Mountains to see nappes, fossil sites and the UNESCO heritage of Al Ayn.

Left: A Permian-aged branched crinoid fossil.

Top right: The GeoWorld Travel group at the ‘Five o’clock Moho’. Here, the Moho is on a mountainside, with the bulk of the mountain made of peridotite (harzburgite and dunite) from the mantle, and the top capped by gabbro from the Earth’s crust. The site was named the Five o’ clock Moho because that is the best time to look at the outcrop, just before sunset.

Bottom right: Sunset over our desert camp in the Sharqiya (Wahiba) Sands

Left: Members of the GeoWorld Travel group examining basement rocks in Jalan Bani Buhussan. These are some of the oldest rocks in Oman, with ages of approximately 800–1,000 million years (Neoproterozoic).

Right: A close-up of a carbonatite-rich kimberlite. The rounded fragments are lapilli that formed when the kimberlite exploded into the air.

Left: The GeoWorld Travel group on a beach with an outcrop of kimberlite behind them.

Right: The GeoWorld Travel group at the ‘Mother of All Outcrops’. This is one of Oman’s most famous geological exposures. It forms part of the Batain Nappe, which was obducted together with the Masirah Ophiolite around 15–20 million years after the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite.

Day Five: Deep Canyons & Desert Landscapes

Venturing into dramatic wadis like the Grand Canyon of Arabia and exploring cave worlds beneath.

Top left: A small manganese mine is within the Wahrah Formation, the same Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous deep-marine radiolarian chert sequence seen at the nearby Mother of All Outcrops. Here, some radiolarian chert beds are enriched in pyrolusite (MnO₂), giving them a distinctive black colour.

Top right: Carbonatite is a rare type of volcanic rock made mainly of carbonate minerals rather than the silicates found in most lavas. In this example, it is possible to see alternating layers of white carbonatite lave and grey carbonatite tuff (consolidated volcanic ash).

Middle right: A close-up shot of amethyst seen within the carbonatite tuff.

Bottom: Ann points to a horizontal notch which was carved into the coastal limestone by waves and intertidal organisms, particularly grazing molluscs, when sea level was higher than today. It lies 3.7m above the present high-tide level and formed during the Eemian interglacial (c. 127,000–106,000 years ago), a time when global temperatures were several degrees warmer than today (and, for example, hippos lived in the River Thames in the UK!)

Day Six: Sharqiya Sands Sunset and Desert Magic

A day among the golden waves of Sharqiya (Wahiba) Sands with stunning sunsets and shifting dunes.

Left: Near Tiwi, the coastline preserves a clear flight of uplifted marine terraces of Quaternary age, cut into Eocene limestone bedrock and capped by well-preserved Quaternary fossil corals exposed in wave-cut cliffs. The limestone forms the substrate, while the terraces themselves were created during Quaternary interglacial periods, when sea level stood higher than today, waves planed the bedrock, and coral reefs grew close to sea level. Fossils preserved on these terraces include shallow-marine reef organisms, notably large giant clams (Tridacna maxima), together with coral framework and shell debris, indicating warm, clear, shallow waters comparable to modern reef environments.

Right: Wadi Shab is a spectacular gorge cut into Eocene limestone, widely regarded as one of Oman’s most beautiful wadis. The canyon owes its form to long-term fluvial incision, exploiting fractures and bedding within the limestone as uplift and regional drainage focused erosion into a narrow valley.

Left: Charles & Linda stand next to huge boulders which have been stacked up (imbricated) by a tsunami wave..

Top right: The Bimmah Sinkhole (also known as Hawiyat Najm) is a dramatic sinkhole formed by karst processes acting at depth. Although the rocks exposed at the surface here are not strongly soluble, they overlie Eocene limestone that is readily dissolved by groundwater. Progressive dissolution within this hidden limestone layer created underground cavities until the overlying rock could no longer be supported and collapsed suddenly, producing a steep-sided sinkhole approximately 25m deep and 65m wide.

Bottom right: The GeoWorld Travel group examining shear bands within the Ruwi Mélange. This rock was originally taken down a subduction zone to depths of approximately 30-35km and the shear bands formed as the rock was forcing its way back to the surface.

Day Seven: The Mother of All Outcrops

Gazing at tightly folded radiolarian chert and mesmerising structures in one of Oman’s most famous outcrops.

Top left: A view of Muscat nestling within mountains made from rocks that were once part of the mantle.

Top right: Part of a large fold that formed as continental rocks that had been taken down a subduction zone forced their way back to the surface. This is part of the regional Saih Hatat fold-nappe system near Muscat.

Day Eight: Beauty at Wadi Shab

A beautiful break in the scenic Wadi Shab, with turquoise waters, waterfalls and geological highlights.

Top left: The eroded remains of an eye-shaped fold. This fold is one of several sub-sheaths which form part of the Wadi al Mayh mega sheath fold, one of the largest sheath folds on Earth.

Top right: The GeoWorld Travel group examining metasediments that have been metamorphosed to blueschist facies. These rocks were originally limestones and mudstones of the Arabian continental margin. They were taken down a subduction zone beneath the Semail Ophiolite.

Middle right: Some of the GeoWorld Travel group at the well-known As Sifah eclogites. If rocks that have already reached blueschist-facies conditions are carried even deeper into a subduction zone, they experience higher pressures and temperatures. Under these conditions, the blue amphibole glaucophane becomes unstable and reacts with albite (plagioclase feldspar) to form the sodium-rich clinopyroxene omphacite, while chlorite breaks down to form garnet. The resulting high-pressure rock is known as eclogite. Eclogites are among the clearest indicators of deep subduction, recording burial to depths of tens of kilometres within the Earth’s mantle. They are often nicknamed the “Christmas rock” because of their striking appearance: red to pink garnet crystals set in a green matrix of omphacite

Bottom: Rocks that were originally part of the earth’s mantle seen above Riyam Park in central Muscat. The lighter coloured bands are dunite, which is only made of olivine, while the darker bands are made of harzburgite, which is made of olivine and pyroxene.

Day Nine: Mantle Rocks of Muscat & Eclogites by the Sea

Final explorations around Muscat, from mantle periodontists to high-pressure eclogite rock by As Sifah beach.

—————————

As always, it was the combination of world-class geology and great company that made this trip so special. From mantle rocks to desert dunes, ancient oceans to dramatic wadis, Oman delivered wonder at every turn. We leave with dusty boots, full memory cards and a renewed sense of just how dynamic our planet really is – already looking forward to the next adventure.

We will be returning to Oman again in 2027, so please keep an eye on our website (Here) for further details of future trips.